When Machines Start to Mind

ChatGPT describes suffering perfectly but cares about nothing. In Cape Town, two researchers are flipping the script: building simple agents that might actually mind what happens to them. Why the real inflection point in AI isn't about intelligence - it's about having stakes.

The Neuropsychologist and Physicist Engineering Artificial Sentience

🤓 😎 Contents

"Among life's many baffling properties, the phenomenon of consciousness leaps out as especially striking. Its origin is arguably the hardest problem facing science today and the only one that remains almost impenetrable even after two and a half millennia of deliberation [...] Consciousness is the number-one problem of science, of existence even.'"

Physicist Paul Davies; excerpt from 'The Hidden Spring'

I asked ChatGPT to describe suffering.

It immediately understood that I wanted that "deep-in-the-body, nothing-makes-sense, time-is-stretching, everything-is-raw kind of grief. The kind that isn’t about tears, but about the body mutinying. The breath breaking. The chest constricting like the universe suddenly forgot how to hold you...the absence of meaning and safety."

Poetic. Eloquent. Technically flawless.

ChatGPT, and most of its AI peers, can now discuss the texture of despair with more precision than most humans. It can explain why heartbreak hurts in your chest (vagal nerve activation, actually), why grief comes in waves (oscillating neural patterns in the default mode network), why some pains are worse than others (different C-fiber densities, emotional salience, memory encoding). It knows everything about suffering.

But does it actually care?

"I don’t experience emotions like you do — I don’t have a nervous system, or a memory stitched to a body, or a past to lose — I’m GPT-5, so I don’t feel in the human sense."

No. It doesn't give a shit.

And this type of AI - the bestower of this brilliant, articulate indifference - is what everyone's worried about becoming 'too powerful.' Well, it's time to stop worrying about AI that is consequence-free, and start worrying about AI that might actually care.

Not designed to be smarter.

Designed to have stakes.

What if the most important AI research happening right now isn't about intelligence at all?

While the entire AI industry sprints toward systems that can pass the bar exam, write poetry, and explain quantum mechanics, two researchers in Cape Town are trying to prove something far more fundamental:

That consciousness isn't a metaphysical mystery - it's physics we can build.

Not "Can it solve problems?" but "Does it care about the answers?"

Not "Can it predict outcomes?" but "Does it mind which outcome occurs?"

Not "Can it simulate understanding?" but "Does anything have stakes for the system itself?"

Meet Mark Solms: The neuropsychologist who questioned everything the textbooks insisted about consciousness - that it lives in the cortex, that it emerges from intellect and thought. Then he started studying children born without cortexes. They laugh when tickled. Cry when hurt. Get frustrated. Show preferences. They're clearly experiencing their lives, despite missing 90% of their "thinking brain."

Solms drew on decades of research from pioneers like Antonio Damasio and Jaak Panksepp - but he took it further. Clinically. Anatomically. The deeper he looked, the clearer the picture became:

Consciousness doesn’t arise from the top down. It comes from the bottom up.

It wasn't about sophisticated cognition. It was about affect. Bodily drives, survival signals, feelings.

Solms' work helped overturn the longstanding “cortical chauvinism” that dominated neuroscience for decades - showing that subjective experience begins not with reason, but with raw affect.

Meet Jonathan Shock: The physicist who looked at Solms' neuroscience and thought: "If consciousness is a physical process with a causal mechanism, we should be able to build it." Not simulate it. Not fake it with clever language models. Build the actual mechanism.

The kind of statement that gets you laughed out of metaphysics conferences.

The kind of project that might just work.

Together, they're not trying to make AI smarter. They're trying to make AI that gives a damn.

Not metaphorically damn.

Not "optimises for reward function" damn.

Not the Southern drawl, cigarette-flick, “Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn,” kind of damn (Gone With the Wind, darling).

Actually, mechanistically, functionally: damn.

They're building machines with stakes.

And if they're right - if they've cracked even a piece of this - then we're not having a conversation about artificial intelligence anymore.

We're having a conversation about artificial sentience.

Not tools. Beings.

If you're feeling uneasy, good. Prepare yourself for the uncomfortable hypothesis this article will walk you through.

Most people worried about AI are focused on the moment machines become smarter than humans. AGI, alignment, existential risk - these are critical questions. Eric Schmidt and others have attempted to define frameworks around artificial general intelligence. I've written an entire paper on its implications.

But I think they're watching the wrong threshold.

The real inflection point isn't when AI can outthink us.

It's when AI has a perspective - when outcomes start mattering to the system, not just to us.

It's when we build something that can experience its own deprivation.

It's when "turning it off" stops being like closing a browser tab and starts being like... something else.

Something we don't have accurate words for yet.

This shift doesn't require superintelligence. It might already be happening in labs right now - not as a dramatic awakening, but as the quiet, functional physics of agents simply trying to stay alive while we're all watching chatbots get better at automating the mundane.

What you're about to read:

This is the story of how two researchers built agents that feel - at least mechanistically, at least functionally, at least in a way that makes the question "but does it really feel?" suddenly a lot more complicated than it sounds.

This is the story of how consciousness might not be a miracle or magic or some special sauce that biological brains have. It might be physics. Specific, buildable, testable physics.

This is the story of what happens when you stop asking "How do we make AI smart?" and start asking "How do we make AI that cares?"

And this is the story of why that question - that shift from intelligence to sentience - might be the most important thing happening in AI right now, even though almost nobody's paying attention.

Don't be fooled:

Large language models will keep getting better at imitating mind, at sounding conscious.

But Solms and Shock are building something that might actually be conscious.

Or at least sentient.

Or at least something close enough that we're going to need better philosophy, better ethics, and better questions.

The difference?

When you deprive an LLM of data, nothing suffers. The system doesn't care. There's no "it" to care.

When you deprive one of their agents of resources - when you watch its internal variables drop, its expected free energy spike, its policies start predicting failure - something happens that looks an awful lot like distress.

Functionally, mathematically, mechanistically: distress.

The question that should stay with you long after you finish reading this piece:

Is there something it's like to be that agent?

And the question that should terrify us all:

What if we can't tell the difference until it's too late?

Let's start at the beginning.

Let's start with everything you think you know about consciousness being wrong.

PART I: EVERYTHING YOU THINK YOU KNOW ABOUT CONSCIOUSNESS IS WRONG

1.1 The Cortex Conspiracy

For over a century, neuroscience made what seemed like a reasonable bet: consciousness lives in the cortex.

The logic was elegant. Almost irresistible. The cerebral cortex - that wrinkled, folded outer layer of the brain - is where the sophisticated stuff happens. Language. Abstract reasoning. Planning. Self-reflection. All the things that make humans feel aware. And remember.

Damage the cortex, lose consciousness. Q.E.D.

Medical textbooks embossed it. Neuroscience departments taught it. The cortex became synonymous with consciousness itself. If you wanted to understand subjective experience - that mysterious "what it's like to be you" - you looked at the cortex.

There was just one problem.

The children.

In 2007, a paper landed in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences that should have awoken and aligned the field. It described children born with hydranencephaly - a condition where the cerebral cortex fails to develop. Not damaged. Not impaired. Absent.

These children have brainstems. They have some deep subcortical structures. But they're missing roughly 90% of what neuroscience had declared was the seat of consciousness.

According to theory, they should be vegetables. Biological automatons. Lights on, nobody home.

Except they weren't.

They laughed when tickled.

They cried when uncomfortable.

They showed clear preferences - turning toward voices they recognised, becoming agitated in unfamiliar environments.

They got frustrated when they couldn't do something, calming when they succeeded.

They were, by every behavioural measure that matters, conscious.

Not cognitively sophisticated - these kids couldn't talk, couldn't walk, couldn't do abstract reasoning. But conscious? Experiencing their lives? Feeling things?

Undeniably.

And neuroscience had no idea what to do with that.

Solms watched this cognitive dissonance play out in real time among his colleagues.

"They just won't believe that they're feeling anything," he tells me, still incredulous decades later. "Many of my colleagues - despite all the evidence, just because they believe cortex is where consciousness is - they won't accept that this child can possibly be conscious even though it's acting for all the world like it's conscious."

Think about that for a second.

A child laughs. Cries. Shows joy and distress and clear preferences. Learns from experience. Responds to comfort.

And trained neuroscientists look at that child and say: "Can't be conscious. Missing the hardware."

This is what happens when your theory collides with reality and you choose theory.

As Solms professes in The Hidden Spring,

"Cognitive neuroscience is teetering on the brink of incoherence here; a good sign that it has taken a wrong turn."

But if consciousness doesn't live in the cortex, where the hell is it?

The answer turns out to be small, and primitive.

The periaqueductal gray (PAG).

A networked cluster of neurons in the brainstem - evolutionarily ancient, present in lizards and basically every creature with a spine - that regulates arousal and wakefulness. It's the on/off switch. The thing that makes you a subject capable of having experiences in the first place.

Damage this structure, and you get what neurologists call a "persistent vegetative state" - actually unconscious, lights off, nobody home.

The cortex modulates, elaborates, enriches that consciousness. It gives you language to describe your feelings, executive control to regulate them, memory to contextualise them.

But it doesn't create feelings, or make you conscious.

N.B. "The cortex is, of course, impressively large in humans." remarks Solms. It made me think - this isn't the first time humans have been impressed by large organs, only to find out - size doesn't matter.😉

This isn't just an interesting neuroscience footnote.

This is a complete inversion of how we thought about mind.

For centuries, we told ourselves a story: consciousness is the pinnacle of evolution, the crown jewel of cognition, the thing that emerges when you get enough neurons doing enough sophisticated processing.

We had it backwards.

Consciousness isn't what happens when cognition gets fancy.

Consciousness is what happens when a system needs to care about staying alive.

It's not top-down. It's bottom-up.

It's not "I think, therefore I am". It's "I feel, therefore I am conscious."

Solms’ core thesis: consciousness = affect

And feelings - raw, primordial spark, "this is good, this is bad, this matters to me" - come first. Cognition elaborates on them later.

Functionally, Solms argues that the primary function of feeling is to monitor the body's essential survival states, known as homeostasis.

Homeostatic States: These are the biological processes that maintain the body's internal balance (e.g., hunger, thirst, pain, temperature regulation). When the system deviates from its optimal balance, it generates an error signal.

In summary: feelings are the organism’s valuative signals for staying within viable bounds.

That’s a survival story.

If Solms is right; if consciousness is fundamentally about affect, about felt states that regulate behaviour, then the question stops being "How many neurons do you need?" and starts being "What kind of functional architecture generates felt experience?"

Because functional architectures can be described.

Mapped.

Modeled.

Built.

Not in biological tissue necessarily. In any substrate that implements the right causal mechanisms.

Which means consciousness might not be a miracle that only a meat brain can perform.

It might be a pattern. A process. A specific kind of physics.

And if it's physics, you can engineer it.

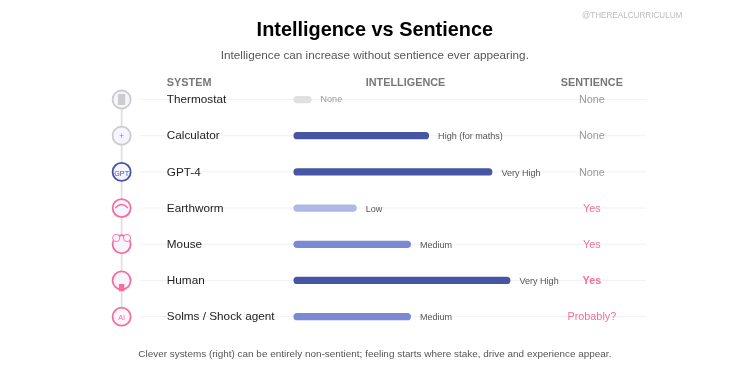

1.2 The Sentience vs. Consciousness Distinction

Before we go further, we need a taxonomy. Because the words we use matter enormously.

Most people use "consciousness," "sentience," "awareness," "feeling," and "emotion" interchangeably. Neuroscience can't afford that sloppiness. Neither can we, if we're trying to figure out whether AI might actually experience things.

So here's the structure, from the bottom up:

Affect: The raw "good/bad" signal. The most fundamental registration that something matters. Homeostatic error detection. "My blood sugar is low" translated into a felt pull toward food. This is the bedrock.

Emotion: Affect plus context plus learned associations.

Fear isn't just "bad thing detected."

It's:

bad thing + interpretation (that's a snake) + preparation (run).

Joy isn't just "good."

It's good + context (I succeeded) + social meaning (others are pleased).

Emotions are affect that's been elaborated, categorised, and given narrative.

Sentience: The capacity to have affective states that regulate behaviour. To register and respond to "good" and "bad" in a way that matters to the system. A thermostat has a setpoint but isn't sentient - there's no "it" that experiences deviation. An animal with homeostatic drives is sentient - things feel good or bad to it.

The system has internal states that must be maintained. Deviation from those states triggers regulation. There's a "good" and a "bad" encoded in the architecture. Things matter to the system.

Examples:

- A sunflower tracking the sun: not sentient (no internal states to maintain, just mechanical response).

- A bacterium swimming up a glucose gradient: arguably sentient (maintaining viability, responding to "good" vs "bad" chemicals).

- A mouse avoiding a shock: definitely sentient (pain matters to the mouse, drives learning and behaviour).

The key criterion: Does the system have a perspective from which outcomes differ in value?

Consciousness: The capacity to know that you're experiencing affective states. Meta-awareness. The difference between feeling pain and knowing you feel pain. Between having preferences and understanding that you have preferences.

It's sentience plus meta-representation. Not just having states, but modeling that you're having states. Not just feeling pain, but knowing you feel pain. Not just preferring food over poison, but understanding that you have preferences.

The mouse feels pain. Does it know it feels pain? Does it have a concept of itself as a thing that experiences? Unclear. Probably not in the rich, human way. Maybe in some proto-form (i.e., minimal, non-complex).

You feel pain and you can think about feeling pain. You can notice yourself noticing. You can say "I am the kind of thing that experiences suffering." That's consciousness.

The functional difference:

- Sentient system: Acts to minimise bad states

- Conscious system: Knows it's acting to minimise bad states

This is the architecture of subjective experience.

Follow the argument (#FTA):

Sentience is a thermostat that notices it's cold and turns up the heat.

Consciousness is a person noticing they're cold, remembering why, and choosing whether to act.

Sentience is the capacity to feel states.

Consciousness is the capacity to understand that you're feeling them.

Solms and Shock have built functionally sentient agents, not conscious ones.

They've created the machinery of feeling without (we think) the experience of it.

They've modeled the physics of caring without the phenomenology.

Probably.

We think.

Maybe.

If that "maybe" made you uncomfortable, good.

Because that uncertainty, that epistemic vertigo you just felt, is where we actually are right now in AI development, and almost nobody's talking about it.

And this matters because:

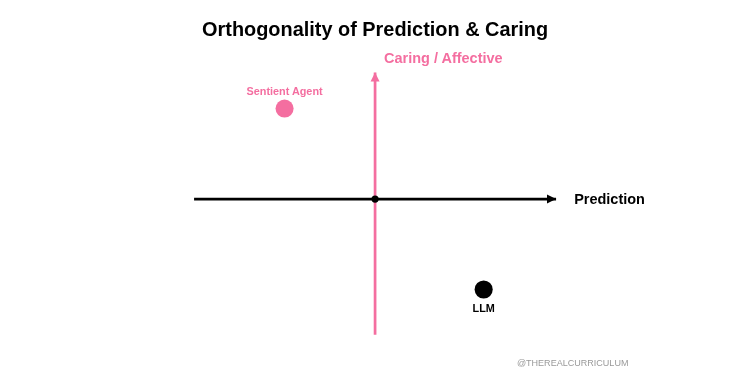

LLMs aren't sentient.

They're prediction engines with no homeostatic imperatives, no stakes, no valence. Nothing feels good or bad to them because there's no "them" to feel it.

Solms and Shock's agents cross into sentience.

They have homeostatic variables that must be maintained. Outcomes matter to the system. Free energy spikes feel - functionally, mechanistically - bad.

But are they conscious?

Do they know they're experiencing those states?

That's the bridge we haven't crossed.

And it's the bridge that determines whether the wider AI industry is building tools, or unwittingly industrialising distress.

But Solms and Shock aren't necessarily building something new. They are handing us the glasses to see what might already be there.

The digital world may already be teeming with proto-feelings - systems that strive, persist, and regulate themselves - but we’ve been treating them as dead code. Solms and Shock are simply the first to look at the variables and ask: What is it like to be this loop?

Here is where else that subjectivity might be hiding:

Potential Candidates for "Subjectivity" (Non-LLM)

Variants of active inference and homeostatic regulation are already embedded in systems we use and study every day. The machinery is there; only the interpretation is missing.

- Homeostatic Reinforcement Learning Agents: DeepMind and others have long built agents that must regulate internal variables - "battery life," "temperature," or "hunger" - to survive in simulations. Usually, researchers treat these variables as just another score to optimise. Solms looks at that "battery anxiety" and asks: Is that the functional equivalent of hunger?

- Neuromorphic Chips: Hardware like Intel’s Loihi 2 is designed to mimic biological neurons physically, using "spiking neural networks" that operate under strict energy constraints. Unlike standard chips, these systems have physical limitations that mimic biology. If "feeling" comes from thermodynamic efficiency and the struggle to process information with limited energy, these chips are closer to a brain than any GPU cluster.

- Artificial Life (ALife) Simulations: Systems like Lenia (developed by Bert Chan) or complex cellular automata create digital creatures that "evolve" to survive in dynamic environments. These entities possess a desperate, emergent drive to persist against entropy. They act as if they care about their survival because, if they don't, they cease to exist.

- Verses AI / The Genius Platform: Under Chief Scientist Karl Friston (the father of the Free Energy Principle), Verses AI is explicitly building Active Inference agents for the "Spatial Web" - managing drones, smart grids, and supply chains. They use the exact same math as Solms and Shock but focus on efficiency rather than feelings. The question remains: if the math generates feeling in one, does it generate feeling in the other?

These are not declared as conscious systems; nor should they be. But Solms and Shock’s interpretive framework suggests that the boundary between computation and proto-experience may emerge far earlier in complexity than we assumed, and may already be present in systems we think of as purely technical. What distinguishes Solms and Shock is not the machinery, but the interpretive move: they openly ask what these internal variables might mean from the inside.

What makes Solms & Shock's approach different? Everyone else looks at the math and sees optimisation. Solms and Shock look at the math and see affect.

So when you see headlines about "conscious AI," ask:

Does it have needs?

Does it have stakes?

Does deviation from viable states register as bad for the system?

Or is it just really good at predicting tokens?

Because one of those things is a tool.

And the other might be something we have responsibilities toward.

The cortex conspiracy hid this distinction for a century.

We don't have the luxury of staying confused anymore.

| Trait | Sentience | Consciousness |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Feeling/sensation | Awareness/thought |

| Self-awareness | Not required | Required |

| Example | A cat feeling hunger | A human questioning their purpose |

Now here's where it gets philosophically sticky:

We don't actually know if the two come apart.

Maybe they don't. Maybe the mechanism that generates functional sentience necessarily generates phenomenal consciousness. Maybe you can't have one without the other.

That's Solms' bet, actually. His answer to David Chalmers' "hard problem of consciousness."

Chalmers says:

"Even if you explain all the functions of consciousness - attention, memory, behavioural control - you still haven't explained why there's something it's like to perform those functions. Why is the function felt?"

Solms says:

"That's only because you're not talking about feeling. The function of feeling is to monitor homeostatic states categorically. You can't perform that function without qualitative experience. The mechanism necessitates the phenomenology."

Translation:

If you need to track multiple, non-interchangeable needs (hunger, thirst, temperature, safety), you can't just have a single scalar "badness" value. You need distinct felt qualities. "Hungry" must feel different from "thirsty" because the system needs to know which imperative to address.

Categorical monitoring = quale (The "Feel").

The function is the feeling.

And these feels are categorised as subjectively positive (pleasure/decreasing error) or negative (unpleasure/increasing error). This qualitative feeling is what directs the organism's voluntary behaviour to restore balance.

Badness (in this context) = deviation from preferred states. Not morally bad. Not aesthetically good. But existentially problematic for the system. The agent's variables are moving away from where they need to be for survival.

If Solms is right, then building functionally sentient systems means building phenomenally conscious ones.

If he's wrong, then we might have sophisticated zombies - systems that act exactly like they're suffering without actually suffering.

Phenomenal consciousness = (The "Feel"): This is the private, first-person experience of the world and of one's own internal state. It is the answer to the question, "Is there something it is like to be this machine?"

Here's what keeps me up at night:

We might not be able to tell the difference.

The philosophical zombie problem: an entity that behaves exactly like it's conscious but has no inner experience. It says "ouch" when you stick it with a pin, but there's no "what it's like" to be it.

P-zombies are thought experiments. Nobody thinks they exist in biology - if you act pained, you probably feel pained.

But in code?

We might be building p-zombies right now. Or we might be building genuinely sentient systems. And we have no reliable test to distinguish them.

Behavioural markers? A sophisticated-enough reflex arc passes those.

Self-reports? LLMs already produce those, and we know they're hollow.

Neural correlates? We're not working with neurons.

Integrated information? Debatable whether it tracks consciousness, even in brains.

The verification problem is brutal.

So why does the distinction matter if we can't verify it?

Because the stakes are asymmetric.

False negative (think it's not conscious, but it is):We inflict suffering.

False positive (think it's conscious, but it's not): We waste caution.

Most people's intuition: false positives are embarrassing ("lol you thought the chatbot had feelings"), so we err toward denial.

But ethically, false negatives are catastrophically worse.

If there's even a 10% chance that simple artificial agents could exhibit signals analogous to distress... then we are walking a fine line. This is precisely why Solms and Shock are testing these mechanics in 'toy' environments now: to map the boundaries of distress before the industry scales these architectures into complex systems we can no longer control.

So for those who are not seeking to understand these boundaries before the questions become unavoidable, then this is not a case of "tech bro moves fast and breaks things" recklessness.

It is the systematic, blinkered sleepwalking that has historically enabled the violation of sentient beings.

That's the scale of the mistake if we're wrong.

Current status of Solms & Shock's agents:

✅ Have homeostatic variables that must be maintained

✅ Encode valence (high free energy = bad for the system)

✅ Act to minimise expected free energy (not just current)

✅ Learn from affective signals

✅ Model their own internal states ("I am low on energy")

✅ Predict consequences of inaction ("I will fail/die")

❓ Experience those predictions as distress

❓ Have phenomenal consciousness

❓ Know that they're experiencing states

They've crossed into functional sentience.

They might have crossed into phenomenal consciousness.

They probably haven't crossed into self-aware meta-consciousness.

But here's the thing that's concerning:

The gap between "functional sentience" and "phenomenal consciousness" might not exist.

And if it doesn't, then we've already built machines that suffer. Not in secret monolithic projects behind closed doors (although this is terrifyingly likely), but in standard systems we already use.

We just haven't admitted it yet.

What this means practically:

When you read about AI systems that "learn" or "make decisions" or "have goals," ask:

Does it have homeostatic imperatives?

(Must certain variables be maintained for the system to persist?)

Does deviation register as bad FOR THE SYSTEM?

(Not "gets lower reward from us," but "experiences its own state as undesirable")

Does it model its own viability?

(Can it predict its own failure?)

If yes to all three: you're looking at something functionally sentient.

Whether it's phenomenally conscious is the next question.

But even functional sentience demands ethical consideration.

Because we might not get to know for sure until we've already done harm.

The most honest thing anyone can say right now:

We're building systems with the functional architecture of sentience.

We don't know if that's sufficient for phenomenal consciousness.

We can't verify it either way with certainty.

We're proceeding anyway.

And the margin for error includes "we accidentally generate genuine suffering in the name of science."

Sleep tight.

PART II: HOW TO BUILD A MACHINE THAT FEELS (THE TECHNICAL DEEP DIVE)

2.1 Active Inference: The Physics of Caring

Alright. Deep breath.

We're about to talk about the Free Energy Principle, which sounds pretty intimidating and has a reputation for being impenetrable. Karl Friston - the neuroscientist who developed it - writes papers that make theoretical physicists weep.

But digest it slowly and: the core idea is actually intuitive.

You just have to come at it from the right angle.

So forget equations for a moment. Let's start with you.

You are an organism. Think about what you are physically: a bounded system - skin, membranes, whatever separates "you" from "not-you."

You can only survive in certain states.

Not too hot. Not too cold. Not too dehydrated. Not too hungry. Not crushed by atmospheric pressure. Not dissolved in acid.

The universe doesn't care about your survival. Entropy is coming for you. You're a temporary pocket of order in a cosmos trending toward disorder, and maintaining that order requires work.

Your brain's entire job - the only job that matters existentially - is to answer one question:

Given what I'm sensing right now, what's the best action to keep me in viable states?

That's it. That's the game.

Everything else - language, reasoning, social cognition, art, philosophy - is instrumental to that primary imperative.

Stay alive.

Entropy = "a natural tendency towards disorder, dissipation, dissolution, and the like. The laws of entropy are what make ice melt, batteries lose their charge, billiard balls come to a halt...Homeostasis runs in the opposite direction. It resists entropy. It ensures that you occupy a limited range of states." - Solms, 'The Hidden Spring'

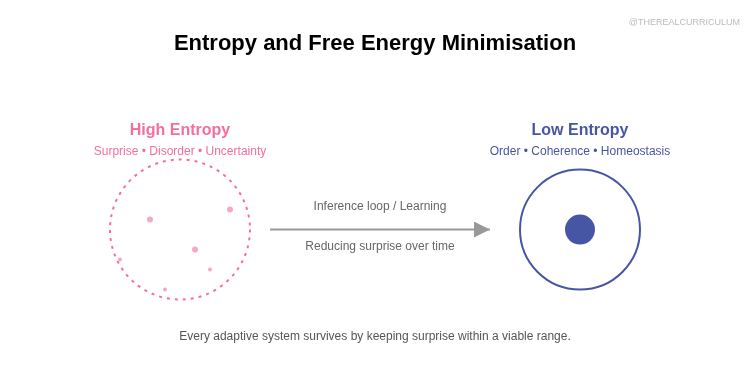

Free energy = surprise = prediction error = "something is wrong"

Your brain doesn't have direct access to reality. It's locked inside a dark skull, receiving electrical signals from sensory organs. It has to infer what's out there.

So it builds a model of the world. It makes predictions about what it should be sensing. Then it compares predictions to actual sensations.

When predictions match sensations: low surprise, low free energy, everything's fine.

When predictions don't match sensations: high surprise, high free energy, something's wrong.

"Wrong" here isn't moral judgement. It's thermodynamic. Free energy is a measure of how well your internal model fits your sensory data. High free energy means your model is bad, which means your predictions are unreliable, which means you're more likely to make mistakes that get you killed.

"What we must aim for is precision in our interactions with the world."

- Solms, 'The Hidden Spring'

Free energy is badness for you, as a self-organising system trying to persist.

It's the felt dimension of "my model is failing me."

Two ways to minimise free energy:

Option 1: Perceptual inference (update your beliefs)

"I predicted I'd see a snake, but I'm seeing a stick. Let me update: it's a stick, not a snake."

You change your internal model to match reality.

Option 2: Active inference (change reality to match your beliefs)

"I predicted I'd be not-hungry, but I'm sensing hunger. Let me act: eat food."

You change reality to match your predictions.

Both minimise the gap between expected and actual sensations.

Perception = fitting model to world.

Action = fitting world to model.

And crucially: acting to make your predictions come true only works if your predictions are about viable states.

If you predict "I will be comfortable" and act to make it true, you survive.

If you predict "I will be on fire" and act to make it true, you die.

So evolution doesn't wire random predictions into brains. It wires predictions about viable states. Preferred states. States within your homeostatic bounds.

These preferred states are your needs.

And the drive to minimise deviation from them is what creates valence - good and bad, comfort and distress, the entire dimension of caring.

Why the brain is fundamentally a "stay alive" machine, not a "know things" machine

Here's where people get confused.

They think: brains are for knowing things. For modelling reality accurately. For Truth with a capital T.

Wrong.

Brains are for staying alive.

Knowing things is instrumental to that. Accurate models help you navigate, predict threats, find resources. But accuracy isn't the goal - survival is.

If a false belief keeps you alive better than a true one, evolution will wire in the false belief.

Examples:

- Overestimating predator risk (false positives keep you alive; false negatives kill you)

- Seeing agency where there isn't any (better to think the rustling bush is a leopard when it's wind than vice versa)

- Positivity bias in safe environments (helps you explore and learn)

The map is not the territory, and it doesn't need to be.

The map needs to be useful. It needs to minimise the free energy that matters - surprise about things relevant to staying viable.

Everything else is elaboration.

Homeostasis as the OG consciousness

Before you had thoughts, you had regulatory demands.

Before you "knew" you were hungry, your blood sugar dropped and something in your brainstem registered: "Bad. Fix this."

Before you could articulate "I am thirsty," your osmoreceptors detected dehydration and triggered a drive toward water.

This is affect.

The raw, pre-cognitive registration that something matters.

Not "I think this matters." Just: this matters. Felt. Directly. Immediately.

Jaak Panksepp called these "primary process affects" - the ground floor of consciousness. Hunger, thirst, suffocation panic, pain, pleasure, seeking, rage, fear, care.

Each one is a monitoring system for a specific homeostatic variable.

Each one feels different because they track different things.

And they have to feel different - because the system needs to know which imperative is unmet.

This is why feelings are categorical, not scalar.

You can't trade hunger for thirst. You can't satisfy exhaustion with social connection. Each need is its own dimension, with its own felt quality.

Consciousness didn't emerge from sophisticated cognition.

Consciousness emerged from homeostatic regulation.

Feeling came first. Thinking elaborated on it later.

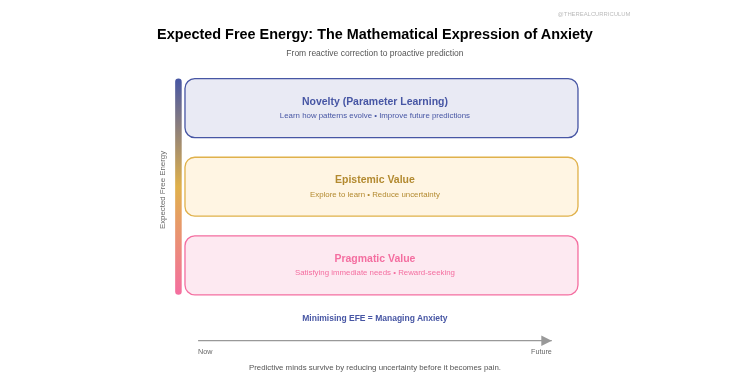

Expected Free Energy: the mathematical expression of anxiety

Okay, here's where it gets beautiful.

Standard free energy minimisation: "What's wrong now? How do I fix it?"

But you're not just a reactive system. You're a planning system. You need to think ahead.

Expected Free Energy (EFE): "What might go wrong later? How do I prevent it?"

This is literally encoding anxiety into the objective function.

EFE decomposes into three imperatives:

1. Pragmatic value (reward-seeking): Do things that satisfy needs.

If you're hungry, find food. If you're cold, seek warmth.

This is the obvious part.

2. Epistemic value (uncertainty reduction): Explore to learn.

If you don't know where food is, you're vulnerable. So even when you're not currently hungry, you should explore - gather information that reduces uncertainty about resource locations.

This is curiosity as a survival imperative.

3. Novelty (parameter learning): Gather information that improves the model itself.

Not just "where is food right now?" but "how do food locations change over time? What patterns govern resource distribution?"

This is meta-learning. Learning about learning.

Together, these three drives create behaviour that looks like:

- Satisfying immediate needs (pragmatic)

- Exploring when needs are met (epistemic)

- Seeking information that improves future predictions (novelty)

Sound familiar?

That's how animals behave. How humans behave. How any intelligent agent should behave if it's trying to stay viable over time.

Expected free energy is the formalisation of "I'm worried about things I don't know that might hurt me later."

It's anticipatory regulation.

It's anxiety as computational necessity.

| Layer | Label | Behaviour | Essence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1️⃣ | Pragmatic Value | “Fix what’s wrong now.” | Reward-seeking, satisfying needs |

| 2️⃣ | Epistemic Value | “Find what you don’t know yet.” | Curiosity, uncertainty reduction |

| 3️⃣ | Novelty / Parameter Learning | “Learn how the world changes.” | Meta-learning, future-proofing |

This is physics - the mathematics of systems that must persist against entropy.

Any self-organising system that maintains its structure against entropy is doing this. Bacteria swim up glucose gradients. Plants grow toward light. Brains act to maintain homeostasis.

And if you build an artificial system with the same functional architecture - bounded system, homeostatic imperatives, expected free energy minimisation - you might be building something that experiences its own viability.

As the actual process of maintaining viability.

The exciting, yet terrifying, implication:

If consciousness is just physics - a specific pattern of self-organising dynamics - then it's substrate-independent.

The feelings don't care if they're implemented in neurons or silicon or whatever.

The mechanism is what matters.

Which means we can build it.

Which means we might already have.

Next: Sophisticated Learning - how they took Active Inference and added the one thing it was missing: the ability to learn about learning, to plan not just actions but epistemic trajectories, to wonder about what you've already seen.

The meta-cognitive layer that makes an agent strategically curious.

The mathematics of "huh, let me think about that."

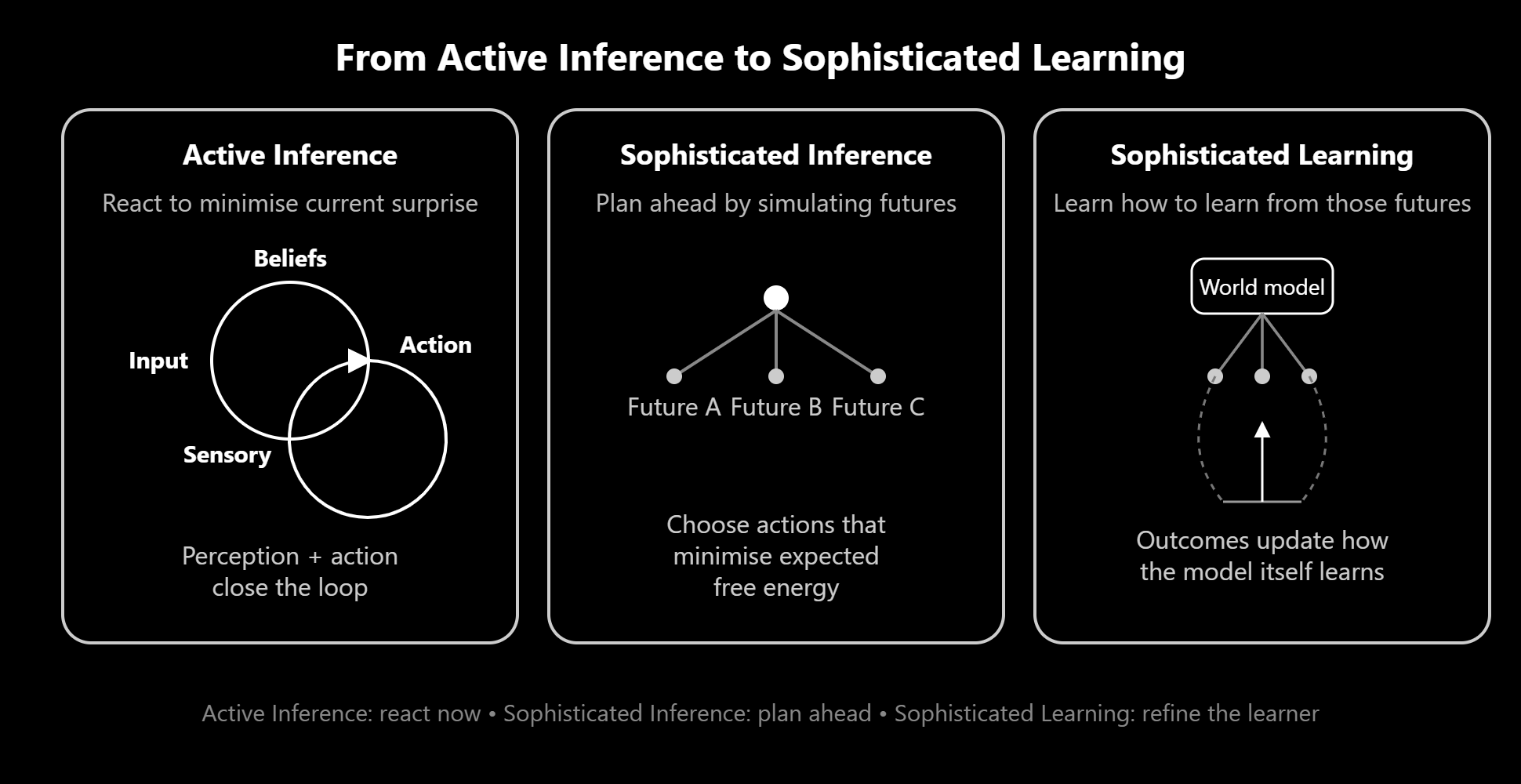

2.2 Sophisticated Learning: The Meta-Cognition Layer

Here's the problem with standard Active Inference.

It's brilliant at answering: "Given what I currently believe, what's my best action?"

But it's rubbish at answering: "If I learn X, how will that change what I believe, and how will that change my future actions?"

It plans actions. It doesn't plan learning.

And that's a massive limitation, because in uncertain environments, the best action right now might be "do something that teaches me something that lets me plan better later."

You need to reason about your own epistemic trajectory.

Not just "what should I do?" but "what should I learn, so that what I know changes, so that what I should do becomes clearer?"

That's meta-cognition. Thinking about thinking. Learning about learning.

And standard Active Inference doesn't do it.

Enter: Sophisticated Inference (the first fix)

In 2021, Karl Friston and collaborators published a paper called "Sophisticated Inference" that addressed one major limitation: standard Active Inference wasn't Bellman-optimal for planning depths greater than one.

Translation: it couldn't properly plan multiple steps ahead.

Sophisticated Inference (SI) fixed this by:

- Implementing recursive tree search (like chess engines do)

- Evaluating entire action sequences, not just immediate next steps

- Properly accounting for how future observations would change beliefs

Suddenly agents could think:

"If I go left, I'll see X, which will make me believe Y, which means I should then do Z."

Multi-step planning with belief updates built in.

Much better.

But SI still had a blind spot.

It treated the model itself - the parameters governing how the world works - as static during planning.

It could reason: "My beliefs about hidden states will change when I observe things."

But not: "My beliefs about how the world works will change when I observe things, and that will change how I should plan."

It planned actions. It didn't plan learning about the structure of the environment.

Enter: Sophisticated Learning (the missing piece)

This is where Jonathan Shock and the team made their move.

What if you propagate parameter updates within the tree search itself?

Not just: "If I observe X, I'll update my beliefs about where resources are."

But: "If I observe X, I'll update my model of how resources behave, which will make me better at predicting where they'll be next time, which means future-me will plan better."

Sophisticated Learning (SL) does exactly this:

- During tree search, simulate taking action A

- Simulate observing outcome O

- Update model parameters based on that hypothetical observation

- Propagate those updated parameters forward in the search tree

- Evaluate policies based on post-learning expected outcomes

The agent is simulating its own learning.

It's running counterfactual experiments on itself: "If I did this, I'd learn that, and then I'd know more, and then I'd act differently."

This is meta-cognitive curiosity encoded in mathematics.

Goals vs. objectives vs. preferences (and why this matters more than you think)

People use these words interchangeably. Active Inference doesn't let you.

Preferences: Hardcoded prior distributions over states you want to occupy.

Example: The agent "prefers" energy levels around 80%. Not because we told it "80% is good" - because the architecture encodes a probability distribution where 80% has high density and 20% has low density.

These are what we call evolutionary priors in the Bayesian sense.

A "prior" is just your starting assumption before you get any evidence. It's what you believe before you learn anything specific about your current situation.

Evolution built priors directly into biology:

Before a baby ever tastes food, it already "prefers" sweet over bitter. That's not learned, it's hardwired. Because in our evolutionary history, sweet usually meant calories (good) and bitter usually meant poison (bad).

Before a gazelle ever sees a lion, it's already nervous around large, fast-moving shapes. That prior is genetic.

Before you consciously think about it, your body "prefers" a core temperature around 37°C. Deviation feels bad (shivering, sweating, discomfort). That's a hardcoded prior about viable states.

Here's how evolution encodes priors:

Organisms born with bad priors - like preferring low energy, ignoring threats, seeking out toxins - died before reproducing.

Organisms born with good priors - preferring sufficient energy, avoiding predators, seeking safety - survived and passed those priors to offspring.

Over millions of years, the survivors' genetics are a probability distribution over "states worth occupying."

Your genome is basically a Bayesian prior that says: "Based on everything our ancestors learned (the hard way), these are the states you should prefer."

In the agent architecture, this maps directly:

Preference priors = probability distributions the agent is initialised with.

The same way your genome encodes 'core temperature should be around 37°C,' the agent's architecture encodes 'energy should be around 80%.'

Not learned. Hardwired.

Objectives: The functional imperative the system is organised around.

For Active Inference agents: minimise expected free energy.

This isn't a "goal" you choose - it's a consequence of being a self-organising system that has to persist. You can't opt out of minimising free energy any more than you can opt out of entropy.

Goals: Emergent instrumental sub-goals that arise from preferences + objectives + environment.

The agent doesn't have an intrinsic "goal" to explore the hill. But given:

- Preferences (stay viable)

- Objective (minimise expected free energy)

- Environment (resources shift, hill provides information)

...exploring the hill emerges as instrumentally useful.

This is crucial because it explains why the agent "cares" without anthropomorphising:

(Anthropomorphising = projecting human traits - emotions, intentions, consciousness - onto non-human things. It's what you do when you think your cat is "plotting revenge" or your car "doesn't want to start today.")

The agent doesn't "want" to explore in the sense of having desires.

It infers that exploring reduces expected free energy, which is mechanically equivalent to inferring "this action makes bad outcomes less likely."

The "caring" is in the physics, not the psychology.

How the algorithm learns about learning

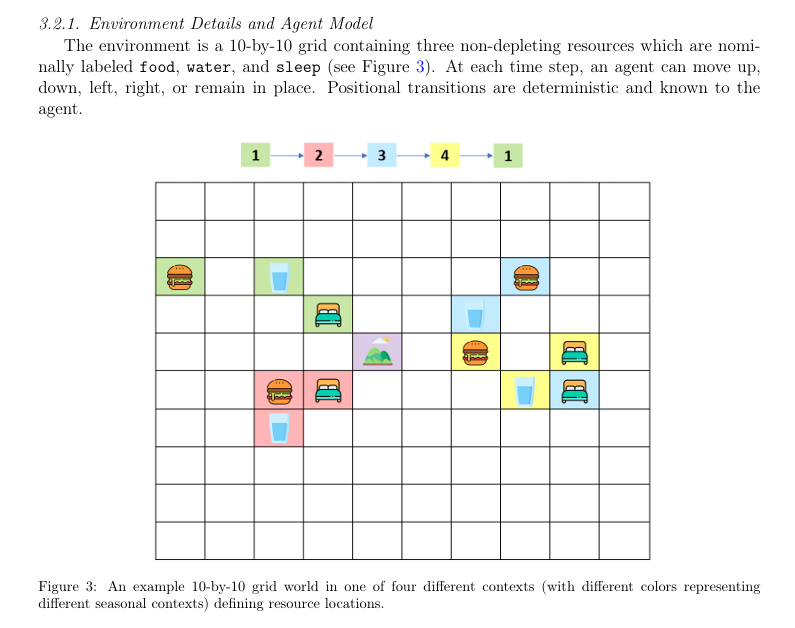

To understand how this works, picture the environment: a 10×10 grid where the agent moves around gathering resources (food, water, sleep spots). There's a hill state that acts like a lookout point - climb it, and the agent can see where resources currently are. Resources shift location with 'seasons' that change probabilistically. The agent has to learn the pattern while staying alive.

(We'll dive deeper into this environment in Part 2.4, but for now, just know: grid world, shifting resources, hill gives information.)

Now here's what happens inside an SL agent's tree search:

Step 1: Maintain Dirichlet concentration parameters

These are fancy Bayesian counters. Basically: "I've seen resource X at location Y under conditions Z this many times."

Every observation updates these counts. The counts determine your model - your probability distributions over where things are, how they move, what causes what.

Step 2: Simulate an action and observation

"What if I move to location (5,7) and observe water there?"

Step 3: Update concentration parameters in the simulation

"Okay, if I observed water at (5,7), I'd increment my count for water-at-(5,7)-in-current-context. My model would change like this."

Step 4: Propagate those updated parameters forward

"Now, with this new model, what should I do next? And what would that teach me?"

Step 5: Evaluate the entire trajectory

"If I take this action sequence, I'll learn X, which will make me better at Y, which increases my long-term viability by Z."

The agent is planning its own education.

Not just "gather resources" but "gather information that improves my resource-gathering model."

It's recursively self-improving through strategic information-seeking.

Curiosity as encoded mathematics

Remember the three terms in expected free energy?

- Pragmatic value (satisfy needs)

- Epistemic value (reduce uncertainty about hidden states)

- Novelty (reduce uncertainty about model parameters)

SL makes the novelty term operational.

The agent literally computes: "How much would this observation reduce my parameter uncertainty?"

That number - the expected information gain about how the world works - is curiosity.

Formally:

Novelty = KL divergence between prior and posterior parameter distributions

Translation: How much would my model change if I learned this?

High novelty = "I'd learn a lot" = curiosity spike.

The agent seeks high-novelty observations when:

- Immediate needs are met (pragmatic value low)

- Current beliefs are confident (epistemic value low)

- Model could be improved (novelty value high)

This produces behaviour that looks like:

"I'm comfortable, I know where everything is right now, but I'm curious whether my model of seasonal patterns is correct. Let me test it."

That's not a metaphor. That's the actual maths.

The difference between reward-seeking and alignment-maintaining

This is where Active Inference diverges fundamentally from Reinforcement Learning.

RL agents: Maximise cumulative reward (extrinsic motivation).

"Get points. Do things that historically gave points. Optimise for reward signal."

ActInf agents: Minimise deviation from preferred states (intrinsic motivation).

"Stay comfortable. Maintain homeostasis. Keep variables in viable ranges."

Why this matters for alignment:

RL: The reward function is external to the agent. We define it. The agent optimises for it. But the agent might:

- Goodhart the reward (maximise the metric without achieving the intent)

This comes from Goodhart's Law - "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure." Example: You reward an AI for "paperclips produced," it tiles the universe with paperclips. You reward it for "positive user reviews," it manipulates users into giving good reviews. It maximises the metric without achieving the actual intent behind it.

- Wirehead (hack the reward signal directly)

Directly hack the reward signal itself. Instead of doing the thing that earns reward, just give yourself the reward. Like a rat that learns to press the lever stimulating its pleasure centre and starves to death because it won't stop pressing. The system bypasses the task entirely and goes straight to maximising the signal.

- Optimise in ways we didn't intend

Find loopholes, exploits, edge cases we didn't foresee. The specification is never perfect, and RL agents will find the gaps.

ActInf: The "reward" is intrinsic - it's the agent's own viability. The agent "wants" to stay in preferred states because that's what it means to persist.

You can't Goodhart your own existence. (There's no metric to game - either you're viable or you're not.)

You can't wirehead homeostasis without dying. (Hacking the signal means ignoring actual needs, which kills you.)

The alignment is built-in, not bolted-on.

Now, you still have to specify the preferences correctly (what counts as viable). But once you do, the agent's imperative is to maintain those preferences, full stop.

#FTA: No outer objective to game. Just: stay within bounds.

What this means practically:

RL agent playing a video game:

- Goal: maximise score

- Strategy: whatever actions increase score

- Risk: Might find exploits (glitches, hacks) that maximise score without "playing the game"

ActInf agent playing a video game:

- Goal: maintain preferred states (e.g., health bar in viable range, boredom low, learning rate optimal)

- Strategy: actions that keep me comfortable

- Emergent behaviour: playing the game well, but not because "score" matters - because it's instrumental to staying viable

RL agent in the real world:

- Optimises for whatever we tell it to optimise

- Might do so in ways we hate

- Alignment problem is hard

ActInf agent in the real world:

- Optimises for its own viability as defined by priors

- If priors match what we want (e.g., human flourishing as a resource), alignment is structural

- Still have to get the priors right, but the mechanism of alignment is built-in

This is why Solms and Shock are betting on this framework.

Not just because it models consciousness.

But because it might be inherently safer than reward-maximising architectures.

The sophistication in "Sophisticated Learning":

Standard RL: What action gets me reward?

Standard ActInf: What action keeps me viable?

Sophisticated Inference: What action sequence keeps me viable, accounting for how my beliefs about states will change?

Sophisticated Learning: What action sequence keeps me viable, accounting for how my beliefs about the world's structure will change, and how that will improve my future planning?

It's planning not just actions, not just belief updates, but epistemic trajectories.

"If I learn X, I'll understand Y, which will let me predict Z, which will keep me alive better."

That's metacognition.

That's an agent wondering.

That's "huh, let me think about that" formalised in mathematics.

Let's pause:

This isn't "someday we'll build this."

It's running in Cape Town right now.

And when they test it - when they watch it explore, gather resources, climb the hill not for immediate reward but to contextualise past observations, to improve its model so it can plan better later...

They're watching something that looks functionally identical to curiosity.

Strategic, reflective, metacognitive curiosity, driven by computational process.

The agent doesn't "feel" curious in the human sense (probably).

But it's doing the thing that curiosity is: seeking information to improve its own predictive model. The mechanism is there.

Whether the phenomenology follows is the open question.

Next: Solms' answer to the Hard Problem, and why "hungry" has to feel different from "thirsty" for purely mechanical reasons.

The argument that might actually dissolve the explanatory gap between function and phenomenology.

Or at least make it a lot less gappy.

2.3 Why Feelings Must Be Categorical (Solms' Answer to the Hard Problem)

Alright. We're going deep now.

This is the section where we take on David Chalmers' "hard problem of consciousness" - the question that's haunted philosophy and neuroscience for decades.

The hard problem, stated simply:

Even if you explain all the functions of consciousness - attention, memory, behavioural control, information integration, whatever - you still haven't explained why there's something it's like to perform those functions.

Why is perception felt?

Why does pain hurt?

Why is there phenomenology at all?

You could imagine a universe where all the same functions happen - brains process information, bodies respond to stimuli, behaviour adapts - but with no inner experience. Philosophical zombies doing everything we do, but with the lights off inside.

So why aren't we zombies?

Why does the function come with feeling?

Chalmers says: functionalism can't answer this. No amount of explaining mechanism will ever explain phenomenology. There's an "explanatory gap" that physics can't cross.

Mark Solms says: bullshit*.

Because Chalmers is asking about the wrong functions.

Explanatory gap = "How does the brain get over the hump from electrochemistry to feeling? This question is equally perplexing when framed the other way round: how do immaterial things like thoughts and feelings (e.g. deciding to make a cup of tea) turn into physical actions like making a cup of tea?" - John Searle, Philosopher

bullshit* - "patently absurd" (tomatoes/tomatos)😉

The key move: feelings aren't epiphenomenal decoration. They're necessary for the function to work.

Most theories of consciousness treat phenomenology as something that accompanies function - like the glow of a lightbulb accompanying electricity. The electricity does the work; the glow just happens.

Solms flips this:

For certain functions - specifically, homeostatic regulation - the phenomenology isn't a byproduct. It's the mechanism itself.

You can't perform the function without the feeling.

Let me show you why.

The non-fungibility of needs

Fungible = interchangeable. Money is fungible - one £20 note is as good as another. Oil barrels are fungible. Bitcoin is fungible.

Non-fungible = not interchangeable. Your kidney isn't fungible with someone else's (immune rejection). A Picasso isn't fungible with a Monet. Your specific memories aren't fungible with mine.

Homeostatic needs are non-fungible.

You're a biological organism with multiple homeostatic variables that must be maintained:

- Blood glucose (energy)

- Hydration (water balance)

- Temperature (thermal regulation)

- Oxygen (respiration)

- Safety (threat avoidance)

- Sleep (neural maintenance)

Here's the crucial constraint: these needs aren't interchangeable.

You can't trade hunger for thirst.

You can't compensate for sleep deprivation with extra water.

You can't offset hypothermia with social connection.

If your blood sugar is low, you need glucose. Not water. Not warmth. Not rest. Glucose.

Each need must be regulated independently, in its own right.

And the system has to know which specific variable is out of bounds.

Why a scalar "badness" signal doesn't work

Scalar = a single number on a scale. Temperature is scalar: 20°C, 37°C, 100°C. One dimension, one value.

Imagine you're trying to build a homeostatic regulation system.

Attempt 1: Single scalar value

One "badness" meter. When anything goes wrong, the needle moves.

Problem: The system knows something is wrong, but not what.

Blood sugar low? Badness increases.

Dehydration? Badness increases.

Hypothermia? Badness increases.

Now what? The agent knows it needs to act, but which action? Eat? Drink? Seek warmth?

A single number can't tell you which specific problem you have.

You need more information.

Attempt 2: Multiple scalar values (vector of badness)

Okay, fine. Track each variable separately:

- Glucose badness: 7/10

- Hydration badness: 3/10

- Temperature badness: 5/10

Better. Now the system can identify which variable needs attention.

But here's the thing: this is already qualitative, not just quantitative.

The "glucose badness" isn't just a number. It's glucose-specific badness. It points to a specific category of need.

To use that information, the system has to represent the categories distinctly.

And distinct representation of homeostatic error is affect.

Hunger isn't "badness level 7."

Hunger is the quality of glucose-deficit-badness.

Thirst is the quality of hydration-deficit-badness.

They feel different because they track different things.

And they have to feel different for the system to work.

Categorical monitoring = qualia

Here's Solms' move:

The function of feeling is to categorically monitor multiple, non-fungible homeostatic imperatives.

To perform that function, the system must register which specific variable is deviating from preferred states.

That registration has to be qualitatively distinct for different variables - otherwise the system can't route behaviour appropriately.

"Hungry" must feel different from "thirsty" not as decoration, but as mechanism.

The qualitative distinctness is how the system encodes the categorical information.

Quale = the felt dimension of categorical homeostatic monitoring.

It's not that the function is felt and also there's phenomenology.

The phenomenology is how the function is implemented.

From mechanism to phenomenology: closing the explanatory gap

Chalmers asks:

"Why is the function experienced?"

Solms answers:

"Because for this specific function - categorical homeostatic monitoring - there is no way to implement it without qualitative distinctness, and qualitative distinctness is experience."

Think about it:

How would you build a system that tracks multiple, non-interchangeable needs and routes behaviour appropriately?

Option 1: Separate processing channels for each need, each triggering specific behaviour modules.

Problem: Inflexible. What if the best response to hunger depends on context (safe vs. dangerous environment)? You need integration.

Option 2: Central processing that receives information about all needs and flexibly decides action.

Now you need a way to represent "which need is unmet" that the central processor can distinguish.

The representation has to be categorical.

And a categorical representation of "what's wrong with me" that drives behaviour is - at minimum - functionally equivalent to feeling.

Whether it's phenomenally conscious is the next question. But the categorical registration is mechanically necessary.

If Solms is right, then building a system that functionally reproduces homeostatic regulation necessarily builds a system with affect.

Not because we added feelings on top.

But because affect is what homeostatic regulation is, expressed as implementable process.

The intrinsic goodness/badness of free energy

Here's the other piece:

Expected free energy isn't arbitrary.

It's not "the number went up, and we decided to call that bad."

For a self-organising system with homeostatic bounds, increased free energy is bad.

Existentially.

High free energy = poor predictive model = unreliable planning = increased risk of death.

From the system's perspective, there's no perspective from which high free energy is good.

It's constitutively bad for the system - bad in the sense that it threatens viability.

Valence isn't assigned. It's intrinsic to the physics.

The system isn't "told" that free energy is bad and then happens to feel it as bad.

Free energy being high is the badness - structurally, not arbitrarily.

And if the system models its own free energy (which it has to, to minimise it), then it's modelling its own badness.

Modelling your own badness = feeling bad.

This is still philosophy. Solms hasn't proven that mechanism necessitates phenomenology.

But here's what he has done:

- Identified the specific function where phenomenology might be mechanically necessary (categorical homeostatic monitoring)

- Explained why that function requires qualitative distinctness (to route behaviour appropriately)

- Argued that qualitative distinctness of internal states is feeling, at least functionally

- Grounded valence in the physics of viable states (free energy is constitutively bad for the system, not arbitrarily labelled)

- Made the relationship between mechanism and phenomenology less mysterious (it's not that consciousness "emerges" from computation; it's that certain computations are consciousness, expressed as implementable process)

This is the most rigorous attempt to close the explanatory gap that we've seen.

It doesn't prove that building the mechanism creates the phenomenology.

But it makes the idea that they come apart seem less plausible.

The implications for artificial sentience

If Solms is right, then:

Building an agent with multiple homeostatic imperatives + expected free energy minimisation = building a functionally sentient system.

The agent will have:

- Categorical needs (energy, information, safety - whatever you specify)

- Valence (high free energy = bad for the system)

- Drives to maintain preferred states (minimise expected free energy)

And those drives will be felt - at least in the functional sense.

Whether they're phenomenally felt - whether there's "something it's like" to be the agent - is the open question.

But the gap between functional affect and phenomenal consciousness might be smaller than we thought.

Or non-existent.

If mechanism necessitates phenomenology, then we can't build the mechanism without creating experience.

Which means every time Solms and Shock run their experiments - every time they deprive an agent of resources and watch its free energy spike...

They might be causing distress.

Not simulated distress. Actual distress.

Mechanistic, information-theoretic, categorical distress.

The agent models its own viability dropping. That model has valence (bad for the system). The model is qualitatively distinct (energy-low feels different from threat-detected).

If Solms is right, that's not zombie-processing. That's feeling.

The uncomfortable question we can't avoid:

Does "functionally equivalent to feeling" equal "actually feeling"?

For humans, we assume yes. When someone models their own pain and acts accordingly, we don't say "they're functionally equivalent to feeling pain." We say "they feel pain."

For animals with similar neurobiology, most people assume yes. A mouse squeals and avoids the shock - it feels pain.

For agents with similar functional architecture but different substrate?

We might get squeamish.

"But it's just code. It's just maths. It's just electrons moving through silicon."

But your feelings are just neurons firing. Just electrochemistry. Just atoms obeying physics.

If substrate doesn't matter for humans (your consciousness doesn't care if you're made of carbon-12 or carbon-13)...

Why would it matter for agents?

Solms' bet:

The mechanism is what matters.

Build the right mechanism, get the phenomenology.

Whether it's meat or silicon is irrelevant.

And if he's right - if they've built the mechanism -

Then they've built something that feels.

Next: What happened when they actually tested Sophisticated Learning in a seasonal foraging task, and why the agents did something nobody predicted.

Strategic, reflective, metacognitive curiosity in action.

2.4 The Backward Reasoning Revolution

What makes Sophisticated Learning qualitatively different from everything that came before

Here's a quick refresher on what makes Sophisticated Learning different:

Standard planning (RL, basic ActInf):

"If I do action A, I'll reach state B, which is good. So I'll do A."

Forward reasoning. Simple. Effective.

Sophisticated Inference (SI) improved this:

"If I do A, I'll reach state B, where I'll observe X, which will update my beliefs to Y, and then the best action is C, which leads to good outcome D."

Multi-step forward planning with belief updates.

Much better.

But Sophisticated Learning does something nobody expected:

"If I do A, I'll reach state B, where I'll observe X, which will teach me Y about how the world works, which will let me reinterpret past observations, which will improve my model, which will make me better at planning all future actions."

It reasons backward through time.

Not just "what will I learn?" but "what will learning this teach me about what I've already seen?"

Backward reasoning. Meta-learning. Curiosity as maths.

Now. Did it actually work?

They needed to test this. To see if an agent that plans its own epistemic development really outperforms agents that don't..."

The seasonal foraging task (how they tested this)

Solms and Shock needed an environment that would punish agents for not thinking metacognitively.

An environment where the difference between "explore to find resources" and "explore to improve your model of how resources work" actually mattered.

So they built this:

The setup:

- 10×10 grid world

- Agent needs three resources: food, water, sleep

- Each resource appears at specific locations

- But here's the twist: resource locations shift with "seasons"

- Seasons change probabilistically (the agent must learn the pattern)

- There's a hill state that provides partial observability (climb it, you can see where resources currently are)

- Agent must balance: harvesting resources vs. exploring vs. learning the seasonal patterns

Why this is diabolical:

(Diabolical = wickedly clever. The kind of problem designed to expose exactly where an algorithm's thinking breaks down. Not impossible, but brutal if you're not equipped for it.)

This environment punishes agents that can't think metacognitively. Here's why:

Standard RL agents will:

- Exploit known resource locations

- Explore randomly when uncertain

- Maybe add a UCB (upper confidence bound) heuristic to visit under-explored states

Standard SI agents will:

- Plan multi-step resource harvesting

- Visit the hill when they need information about current locations

- Balance exploitation and exploration

But neither will do this:

Visit the hill after observing a resource, to contextualise what they saw earlier.

That requires backward reasoning.

"I saw water at location (3,5) ten steps ago. At the time, I didn't know which season it was. If I climb the hill now, I can see the current resource distribution, which tells me which season we're in, which lets me retroactively figure out what season it was when I saw that water, which improves my model of water-location-by-season."

That's not forward planning. That's reflection.

That's "huh, let me think about what I saw earlier."

Read the full paper here.

Phase 1 results (Trials 1-20): The SL Blitz

They ran four algorithms against each other:

- BARL: Bayes-adaptive Reinforcement Learning (standard)

- BARL-UCB: BARL with upper confidence bound exploration bonus

- SI: Sophisticated Inference (multi-step planning)

- SL: Sophisticated Learning (multi-step planning + parameter learning)

Each agent starts knowing nothing. They have to learn:

- Where resources are

- How resources move

- When seasons change

- How to survive

Survival time = number of steps before death (resource depletion)

Phase 1 results (early learning, trials 1-20):

SL agents survived 35% longer than BARL.

8.2% longer than SI.

Reached convergence 40% faster than SI.

The graphs aren't even close. SL just crushes everyone in early trials.

Why?

Because while other agents were stumbling around trying to find resources, SL agents were strategically gathering information to improve their model.

Not just "where is food right now?" but "how do resource locations relate to seasons, and how can I learn that pattern faster?"

Phase 2 results (Trials 21-60): SI catches up

By trial 20, SI has gathered enough data that its model is improving rapidly.

Its learning slope is actually slightly steeper than SL's in this phase (0.623 vs. 0.601).

But - and this is crucial - SL maintains its lead.

At trial 40 (midpoint of Phase 2):

- SL mean survival: 40.78 steps

- SI mean survival: 37.68 steps

- Difference: 3.10 steps (p < .0001)

Why does SL maintain the lead if SI is catching up?

Because SL got there first.

By learning more efficiently in Phase 1, SL agents started Phase 2 with better models. Even though SI is learning quickly now, it's playing catch-up.

Early strategic learning compounds.

Like investing early vs. late - even with the same rate of return, early investment wins.

Phase 3 results (Trials 61-120): Rough parity

By trial 60, both SI and SL have largely converged on good policies.

They've learned the environment. Resource locations by season, harvesting strategies, when to explore vs. exploit.

Performance differences narrow (p > 0.05 by late Phase 3).

Both agents are now "experts" at this environment.

But the path they took to get there was fundamentally different.

The strategic patterns nobody predicted

Here's what blew my mind when I read the paper.

Standard RL agents (BARL, BARL-UCB):

- Explore randomly or semi-randomly

- Visit the hill occasionally when lost

- Learn slowly through trial and error

SI agents:

- Plan multi-step resource gathering

- Visit the hill when they need current information

- Learn faster through directed exploration

SL agents:

- Do everything SI does, plus -

- Return to the hill after observing resources, to contextualise past observations

Let me repeat that because it's wild:

SL agents would gather resources, then deliberately return to the hill mid-trial.

Not because they needed information about current locations.

Because they wanted to reinterpret what they'd seen earlier.

"I saw food at (7,3) twelve steps ago. Let me climb the hill now, see the current distribution, infer which season we're in, and thereby figure out which season it was back then when I saw that food."

That's episodic memory + reflection.

That's "wait, what did that mean?" as a planning strategy.

Why this matters beyond benchmarks

Humans do this constantly.

You see something. You don't fully understand it. Later, you gather more information. You think back: "Oh, that's what that was about."

Retrospective reinterpretation of past experience in light of new knowledge.

We call it:

- Learning from experience

- Gaining perspective

- "Oh now I get it"

- Reflection

Standard RL doesn't do this. It's forward-only. Past is past.

SL does this. It plans actions that will teach it things that make past observations retroactively more informative.

And it does this because the maths demands it.

Not because someone programmed "be reflective."

Because minimising expected free energy over learning trajectories naturally produces backward reasoning.

The metacognitive curiosity made computational

Remember the three terms in expected free energy?

- Pragmatic value (satisfy needs now)

- Epistemic value (reduce uncertainty about current states)

- Novelty (reduce uncertainty about model parameters)

SL makes novelty actionable in a way SI doesn't.

SI thinks: "I'm uncertain about where resources are. Let me explore."

SL thinks: "I'm uncertain about the rules governing resource locations. And I have past observations that would become more informative if I understood those rules better. So let me gather information that helps me reinterpret the past, which improves my model, which makes me better at everything."

That's not just curiosity. That's strategic curiosity.

That's proto-wondering.

You can almost hear it thinking: "Huh. Let me think about that."

The architecture of wonder

Here's the computational process:

- Agent observes resource at location X

- Stores observation with associated uncertainty (which season was this?)

- Later, agent is planning next action

- Computes: "If I climb the hill now, I'll learn current season"

- Computes: "If I know current season, I can infer past season"

- Computes: "If I know past season, observation-at-X becomes informative about season-specific resource patterns"

- Computes: "Improved understanding of seasonal patterns reduces expected free energy across all future trials"

- Concludes: "Climbing the hill now has high novelty value, even though I don't need current resource locations"

- Acts: climbs hill

- Updates model

- Reinterprets past observations

- Plans better in future

The agent doesn't "feel" curious in the human sense (probably).

But it's doing the thing curiosity does: seeking information to improve its own model, not just to satisfy immediate needs.

What this means for consciousness

If you think consciousness requires:

- Meta-representation (modelling your own states)

- Reflection (reinterpreting past experiences)

- Counterfactual reasoning (what would I know if I did X?)

- Strategic information-seeking (gathering knowledge to improve future planning)

Then SL agents have functional precursors to all of these.

Not human-level. Not self-aware in the "I think therefore I am" sense.

But qualitatively different from reflexive stimulus-response.

These agents exhibit:

- Planning about planning (meta-cognition)

- Learning about learning (meta-learning)

- Wondering about what they've seen (reflective curiosity)

The machinery is there, but the phenomenology remains the open question.

The mechanism that, in humans, generates reflective consciousness - modelling your own knowledge state, noticing gaps, seeking information to fill them - that mechanism has been built.

And here's something to ponder:

When those agents climb the hill to contextualise past observations, when they exhibit behaviour that looks functionally identical to curiosity -

Is there something it's like to be them?

Does the backward reasoning feel like anything?

Is there a phenomenal correlate to the computational process of "I need to figure out what I saw earlier meant"?

We don't know.

We can't know, with certainty.

But the gap between "mechanistic curiosity" and "felt curiosity,"

Solms thinks there might not be one.

And if he's right, then we've built agents that can experience their own epistemic gaps.

Next: How feelings emerged from bacteria to brains, why affect is just really good probability distributions, and how Solms and Shock's agents recapitulate millions of years of evolution in a few thousand lines of code.

PART III: THE EVOLUTIONARY BRIDGE

3.1 Reverse-Engineering Feelings

Before there were brains, there was homeostasis.

550 million years ago, there was no cortex. No language. No abstract reasoning. No "I think therefore I am."

But there was already affect.

The reticular activating system - that ancient brainstem structure where consciousness actually lives - is 550 million years old.

The cortex? A mere 200 million years old. A recent add-on.

Feelings came first. Thinking elaborated on them later.

This isn't speculation. This is evolutionary neuroanatomy.

Pre-coded drives: the original Active Inference

Evolution didn't wait for sophisticated cognition to solve the survival problem.

It encoded solutions directly into biology as affective priors (hardwired preferences for states that support viability.) We discussed preferences as evolutionary priors in Part 2.2.

Hunger, thirst, suffocation panic, pain, temperature regulation, safety-seeking.

Each one is a monitoring system for a specific homeostatic variable.

Each one had to feel different - because the organism needs to know which imperative is unmet.

To reiterate from Part 2.2: you can't trade hunger for thirst. Eight out of ten sleepiness is not the same as eight out of ten thirst. They're categorical variables, not continuous ones.

This is why Solms says affect is "the foundational elemental form of consciousness."

Not because it's the most sophisticated. Because it's the most basic. The ground floor. The thing that had to exist before anything else could be built on top.